From Backchannel

After 1.7 million miles we’ve learned a lot — not just about our system but how humans drive, too.

About 33,000 people die on America’s roads every year. That’s why so much of the enthusiasm for self-driving cars has focused on their potential to reduce accident rates. As we continue to work toward our vision of fully self-driving vehicles that can take anyone from point A to point B at the push of a button, we’re thinking a lot about how to measure our progress and our impact on road safety.

One of the most important things we need to understand in order to judge our cars’ safety performance is “baseline” accident activity on typical suburban streets. Quite simply, because many incidents never make it into official statistics, we need to find out how often we can expect to get hit by other drivers. Even when our software and sensors can detect a sticky situation and take action earlier and faster than an alert human driver, sometimes we won’t be able to overcome the realities of speed and distance; sometimes we’ll get hit just waiting for a light to change. And that’s important context for communities with self-driving cars on their streets; although we wish we could avoid all accidents, some will be unavoidable.

The most common accidents our cars are likely to experience in typical day to day street driving — light damage, no injuries — aren’t well understood because they’re not reported to police. Yet according to National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) data, these incidents account for 55% of all crashes. It’s hard to know what’s really going on out on the streets unless you’re doing miles and miles of driving every day. And that’s exactly what we’ve been doing with our fleet of 20+ self-driving vehicles and team of safety drivers, who’ve driven 1.7 million miles (manually and autonomously combined). The cars have self-driven nearly a million of those miles, and we’re now averaging around 10,000 self-driven miles a week (a bit less than a typical American driver logs in a year), mostly on city streets.

In the spirit of helping all of us be safer drivers, we wanted to share a few patterns we’ve seen. A lot of this won’t be a surprise, especially if you already know that driver error causes 94% of crashes.

If you spend enough time on the road, accidents will happen whether you’re in a car or a self-driving car. Over the 6 years since we started the project, we’ve been involved in 11 minor accidents (light damage, no injuries) during those 1.7 million miles of autonomous and manual driving with our safety drivers behind the wheel, and not once was the self-driving car the cause of the accident.

Rear-end crashes are the most frequent accidents in America, and often there’s little the driver in front can do to avoid getting hit; we’ve been hit from behind seven times, mainly at traffic lights but also on the freeway. We’ve also been side-swiped a couple of times and hit by a car rolling through a stop sign. And as you might expect, we see more accidents per mile driven on city streets than on freeways; we were hit 8 times in many fewer miles of city driving. All the crazy experiences we’ve had on the road have been really valuable for our project. We have a detailed review process and try to learn something from each incident, even if it hasn’t been our fault.

Not only are we developing a good understanding of minor accident rates on suburban streets, we’ve also identified patterns of driver behavior (lane-drifting, red-light running) that are leading indicators of significant collisions. Those behaviors don’t ever show up in official statistics, but they create dangerous situations for everyone around them.

Lots of people aren’t paying attention to the road. In any given daylight moment in America, there are 660,000 people behind the wheel who are checking their devices instead of watching the road. Our safety drivers routinely see people weaving in and out of their lanes; we’ve spotted people reading books, and even one playing a trumpet. A self-driving car has people beat on this dimension of road safety. With 360 degree visibility and 100% attention out in all directions at all times; our newest sensors can keep track of other vehicles, cyclists, and pedestrians out to a distance of nearly two football fields.

Intersections can be scary places. Over the last several years, 21% of the fatalities and about 50% of the serious injuries on U.S. roads have involved intersections. And the injuries are usually to pedestrians and other drivers, not the driver running the red light. This is why we’ve programmed our cars to pause briefly after a light turns green before proceeding into the intersection — that’s often when someone will barrel impatiently or distractedly through the intersection.

In this case, a cyclist (the light blue box) got a late start across the intersection and narrowly avoided getting hit by a car making a left turn (the purple box entering the intersection) who didn’t see him and had started to move when the light turned green. Our car predicted the cyclist’s behavior (the red path) and did not start moving until the cyclist was safely across the intersection.

Turns can be trouble. We see people turning onto, and then driving on, the wrong side of the road a lot — particularly at night, it’s common for people to overshoot or undershoot the median.

In this image you can see not one, but two cars (the two purple boxes on the left of the green path are the cars you can see in the photo) coming toward us on the wrong side of the median; this happened at night on one of Mountain View’s busiest boulevards.

Other times, drivers do very silly things when they realize they’re about to miss their turn.

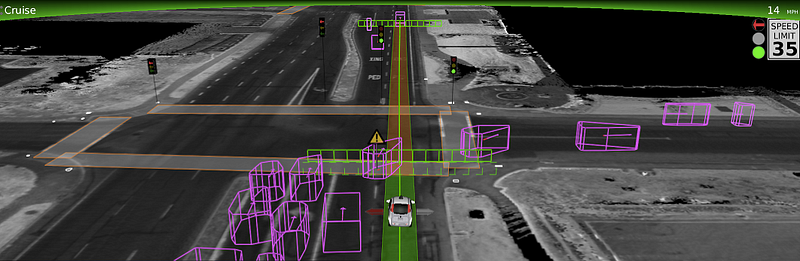

A car (the purple box touching the green rectangles with an exclamation mark over it) decided to make a right turn from the lane to our left, cutting sharply across our path. The green rectangles, which we call a “fence,” indicate our car is going to slow down to avoid the car making this crazy turn.

And other times, cars seem to behave as if we’re not there. In the image below, a car in the leftmost turn lane (the purple box with a red fence through it) took the turn wide and cut off our car. In this case, the red fence indicates our car is stopping and avoiding the other vehicle.

These experiences (and countless others) have only reinforced for us the challenges we all face on our roads today. We’ll continue to drive thousands of miles so we can all better understand the all too common incidents that cause many of us to dislike day to day driving — and we’ll continue to work hard on developing a self-driving car that can shoulder this burden for us.

Chris Urmson is director of Google’s self-driving car program.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.